Picturing Health

Group Exhibition, Best Practice, 2024

Picturing Health is a group exhibition featuring seven San Diego-based artists making work about health, illness, and disability. Artists in the exhibition include Philip Brun Del Re, Maria Mathioudakis, Bhavna Mehta, Tatiana Ortiz-Rubio, Elizabeth Rooklidge, Akiko Surai, and Christina Valenzuela.

Working in painting, sculpture, photography, and textile, together they ask, what does it mean to represent the vulnerabilities of the body in visual form? The artwork in this exhibition largely avoids linear narratives of recovery, problematizing the dominant ideology of "good" health and recognizing that “ill" health—whether temporary or permanent—is an inevitability. Health is a continuum, constantly in flux, and its complications constitute a foundational facet of human experience.

Health thus becomes a subject for interrogation, ripe for artistic inquiry. The artists in Picturing Health question how we access the care we need, how experiences of time and space are affected by disability, and how the ill or disabled body can become a site of agency and discovery. Anchored in each artist’s personal experience, the works collectively affirm difference while advocating for interdependence, intimacy, and care.

Photos: Daniel Lang

Philip Brun Del Re, DRUG FREED BODY, 2024, house paint, graphite, and water, 48 x 52 in.

“In this wall drawing, I repurpose and adapt a found t-shirt slogan, ‘DRUG FREE BODY,’ which felt like an absurd and outdated statement. The adaptation relates to my interest in how substances can heal and liberate in a variety of different ways. I find personal connection with these words in relation to the chemotherapy treatment I underwent last year.”

Philip Brun Del Re, Surrender, 2024, sweat-stained undershirt and t-shirt sleeves, thread, wooden dowel, spray paint, and metal flag pole holder, 117 x 6 x 21 in.

“Surrender is a flag-like sculpture: an evidential, material record of my body’s stress, strain, exhaustion, and exertion during physical labor. The flag simultaneously operates as an emblem of the sudden upheaval of my labor in the face of a surprising cancer diagnosis. Mounted on the wall, it stands as a reminder of bodily surrender to care in times of overexertion and illness. The pit stain, a visceral record of anxiety and shame, is highlighted instead to indicate rest and transformation. Ultimately, the white flag—a symbol of defeat—oddly enough brings about release.”

Maria Mathioudakis and Maddie Woods, Brochure (San Diego) and Brochure (Tijuana), 2024, digital prints on handmade paper, 21.5 x 30 in. each

“The source material for Brochure (San Diego) and Brochure (Tijuana) are illustrations created by Federation of Feminist Women’s Health Center layworker and San Diegan Suzann Gage L Ac, RNC, NP. Both diptychs emerge from the study of the images created for the FFWHC publications about self-examination. The FFWHC was founded in 1960s Los Angeles, when a group of laywomen, known as the Federation of Feminist Women’s Health Centers, created the plastic speculum now used throughout the world.

In the United States, the gynecological sciences emerged alongside African chattel slavery. Although, laywomen and midwives had performed abortions and other sexual-health practices in the premodern world. The professional field of gynecology, as practiced by medical doctors today, was developed through the torture of enslaved women in the mid-1800s in Alabama. The low-cost, plastic speculum developed by the FFWHC was an alternative tool which allowed for a new form of self-examination outside of the violent history of gynecological science. Although FFWHC laywomen created elaborate practices for the communal use of the plastic speculum, hoping to find some immanent truth within themselves and each other, they ultimately found that even their de-mystified bodies were always and already socially constructed by notions of sex and gender.

FFWHC formerly had clinics across the southwest, including facilities in San Diego and Tijuana. These works were created as celebrations and meditations on these local histories. Both Brochure (San Diego) and Brochure (Tijuana) were produced collaboratively by Maria Mathioudakis and Maddie Woods.”

Bhavna Mehta, I Found a River in My Body #1 and I Found a River in My Body #2, 2022, hand embroidery on printed silk, 60 x 51 in. each

“How can we read a disabled body as a place? My before- and after-surgery X-rays from almost forty years ago become a landscape stitched with the colors that evoke mountains, meadows, deserts, rivers, trees, and rocks. As I align myself with features that shape and form the land, my body returns to a primal place where injury can sit alongside discovery.”

Tatiana Ortiz-Rubio, Entre nosotros, 2024, saved objects

“The installation Entre Nosotros (Between Us) explores the complex relationship my partner and I have with our child’s medical and sensory equipment as a consequence of her multiple disabilities. The work stems from the realization that we never discarded the present objects, and the implications of having kept them. These objects, which at first meeting feel alien, sterile and intimidating, have become commonplace to us—relics of our family’s life. Entre Nosotros explores these objects as visual representations of our intimacy between caregivers and recipients, of the story between us, of the barriers between us, of the dialogue between. They are embodiments of our hopes, pain, fears, and endeavors. Some objects have even become extensions of our disabled child’s identity, such as the communication symbols. Access to alternative communication is significant for non-speakers and the intellectually disabled in a world where they are told what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and presumed incompetent or unable to know their own needs or wants. Words allow disabled individuals to invoke their right to have opinions and self-determination. The word ‘more’ stands as a challenge, a reality, and a foretelling.”

Tatiana Ortiz-Rubio, Non-compliant, 2024, graphite and charcoal on polypropylene paper, 26 x 40 in.

“This drawing came unplanned, as a result of the frustrations, indignation, and impotence that accumulate from living in a deeply ableist world. The complexities of caring and advocating for a child with multiple disabilities and health conditions are eclipsed when compared to the emotional fatigue and societal alienation resulting from dealing with a world that, for the most part, devalues a disabled person’s life and rights. This work explores the mental health difficulties that caregivers experience by the pressures put on them from society, and questions the incongruous reality of the caregiver being told repeatedly to ‘have hope,’ ‘be optimistic,’ and take it ‘day by day,’ while subtly being rejected, excluded, and ignored at the same time.”

Elizabeth Rooklidge, Searching, 2024, inkjet prints, 8 x 10 in. each

“This series of digital collages mines the dizzying complexity of managing our health in the age of the internet. The project draws on a wide range of material—from 15th-century medical illustration to early x-rays, from pseudoscientific cartoons to contemporary stock photography—all sourced online. The works suggest the long history of looking for answers when faced with health issues, as well as the contemporary surfeit of information (and misinformation) at our fingertips. As a person with multiple chronic illnesses, I find the internet to be a place where hope, fear, possibility, and frustration coexist uncomfortably—it is a digital space that seems to offer answers, yet most often yields more questions.”

Akiko Surai, Untitled (Mass 02), 2024, mixed fibers and beading on stone, 8 x 6 x 6

“All that you touch. You Change. All that you Change, Changes you. The only lasting truth is Change.” Octavia Butler

“The embroidery and beading of Untitled (Mass 02) creep like fungus or lichen across its stone. As the piece develops, the foam ‘body’ holds and grasps the stone, learning from and knowing the surface, eventually circluding and absorbing it.

These works draw from natural examples of non-linear growth as an analog to my experience healing from traumatic brain injury. Thinking of my body and the mixed conglomerates of the Mass series as responsive, complex organisms, with the ability to metabolize and alchemize, instead of a malfunctioning machine allows us both to explore healing as a process of growth and expansion instead of a return to an untouched state.”

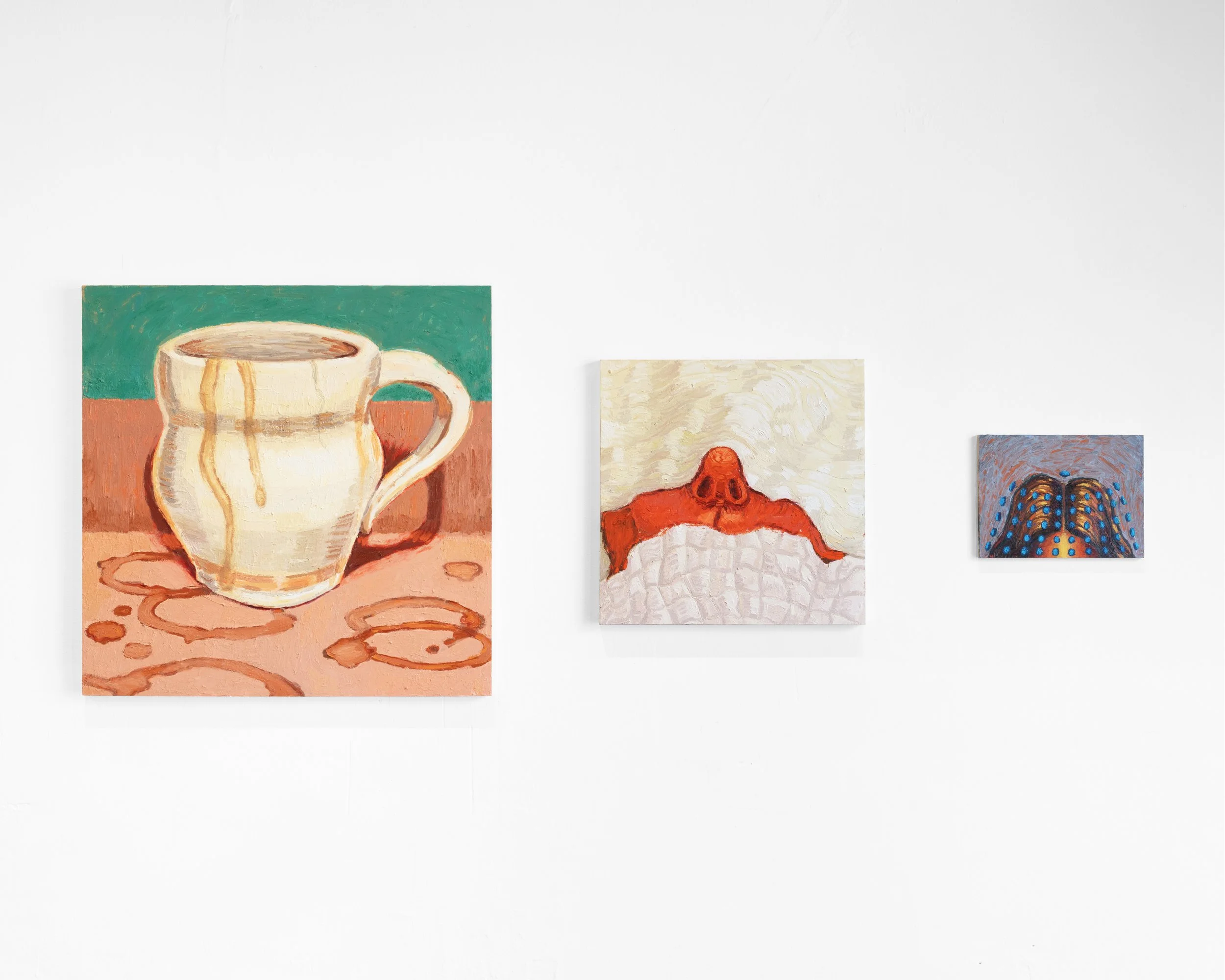

Christina Valenzuela, Untitled (My Coffee Cup), 2024, oil on wood, 40 x 40 in.; Sleep Study, 2023, oil on wood, 25.75 x 25.75 in.; Energy Field, 2023, oil on wood, 12 x 16 in.

”I consider all of my paintings in this show self-portraits. In making work, the thing that occupies my mind (literally and figuratively) is narcolepsy: a neurological disorder that affects the brain’s ability to control sleep-wake cycles. Disks surrounding the top of the head symbolize the electrodes of an electroencephalogram, which measures electrical brain activity and helps diagnose and understand neurological and sleep disorders. Sleep absorbs my figure, needing to rest so badly that the only thing that matters is making sure I breathe. I’m completely consumed in that moment and, metaphorically, in my life. My coffee cup, a source of wakefulness and means of coping, is empty and exhausted—the coffee goes so fast, just like my energy. Painting these images offers a means of transformation and reorientation. Illustrating honest accounts of persistent illness allows me to process, solidify, confront, and embrace these mental and physical experiences that shape my life, giving them a new body and making space in my own.”